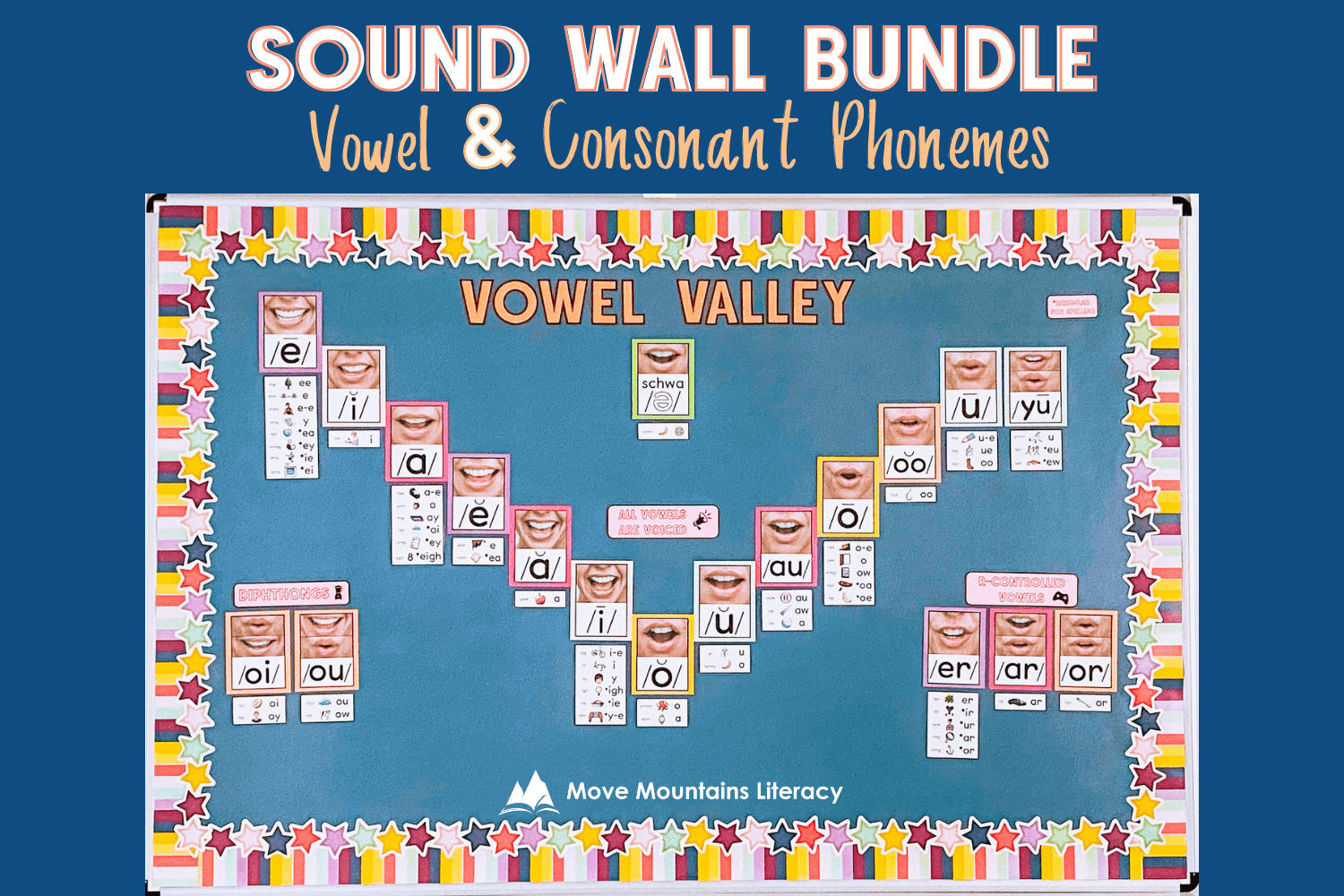

What is a Sound Wall?

Vowel and Consonant Sounds

Don’t you just love a good “comeback” story? You know, the kind where the main character is living their best life, and out of nowhere, an unforeseen force knocks them off their pedestal. Then the hero spends the rest of the plot trying to get back on top while learning valuable lessons along the way. In education, phonics is the underdog making its swift return to the forefront of literacy instruction. Phonics instruction has evolved during its time underground, and the Sound Wall is one of its newest features.

The Sound Wall is the phonetic alternative to a Word Wall. The Sound Wall provides educators with a framework to teach speech sounds and the graphemes (letters) used to represent those sounds. Studying the unique features of these sounds will help young students as they read and write. Many schools that provide literacy instruction using the Whole Language or Balanced Literacy approach require teachers to incorporate a Word Wall. This blog post aims to explain the components of a Sound Wall. To learn more about the similarities and differences between a Sound Wall and Word Wall, check out my blog post: “Sound Wall vs. Word Wall.”

Organized by Sound

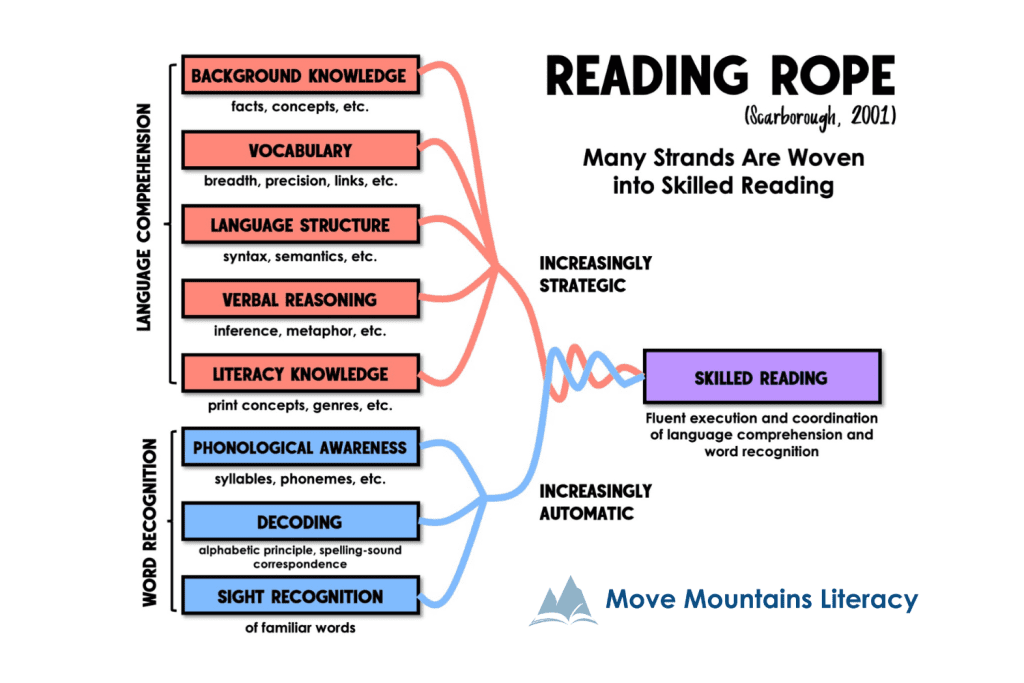

Not surprisingly, a Sound Wall organizes words by sound. Many students come to school with the ability to hear and recognize sounds in their native language. They respond to hearing their name, recognize their favorite TV show jingle, and choose what they want to eat for a snack out of a list of choices. Effective literacy instruction helps children understand that our language’s speech sounds (phonemes) are represented by letters (graphemes). A Sound Wall helps bridge the gap between children’s oral language skills and the advanced knowledge they need to become successful readers and writers.

Identifying and describing speech sounds can be an abstract concept for children and adults. To make sounds more concrete, bring attention to what a sound looks like and what it feels like. Students can use a mirror to see what their teeth, tongue, and lips are doing when they make a sound. Students can also check if their vocal cords vibrate by gently placing their fingers on the front of their neck. When their vocal cords vibrate, the sound is voiced. When their vocal cords do not vibrate, the sound is unvoiced. Using this multisensory approach (visual, tactile) to learn about speech sounds will help students remember and distinguish letter sounds when reading and spelling. These practices are also critical to implementing a Sound Wall effectively.

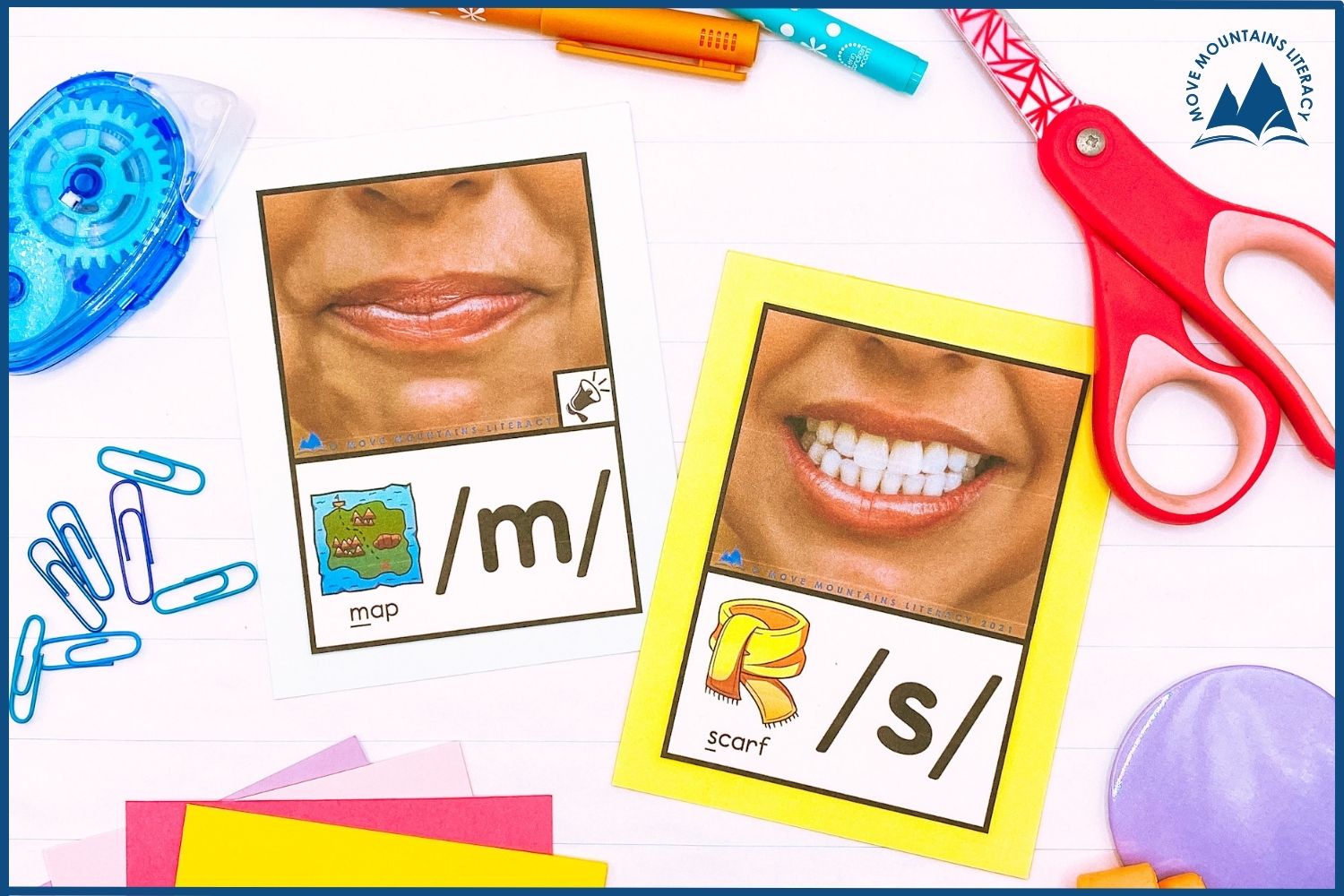

Many of the sounds in the English language are categorized as vowel or consonant sounds. Vowel sounds typically cause your mouth to open, and your vocal cords vibrate. Consonant sounds usually block the airflow like /m/ as in “map;” or partially block the airflow like /s/ as in “scarf.” Consonant sounds can be voiced (vibrate your vocal cords) or unvoiced. A Sound Wall organizes sounds by separating the vowels from the consonants. Furthermore, the sounds are grouped according to place and manner of articulation.

Vowel Sounds

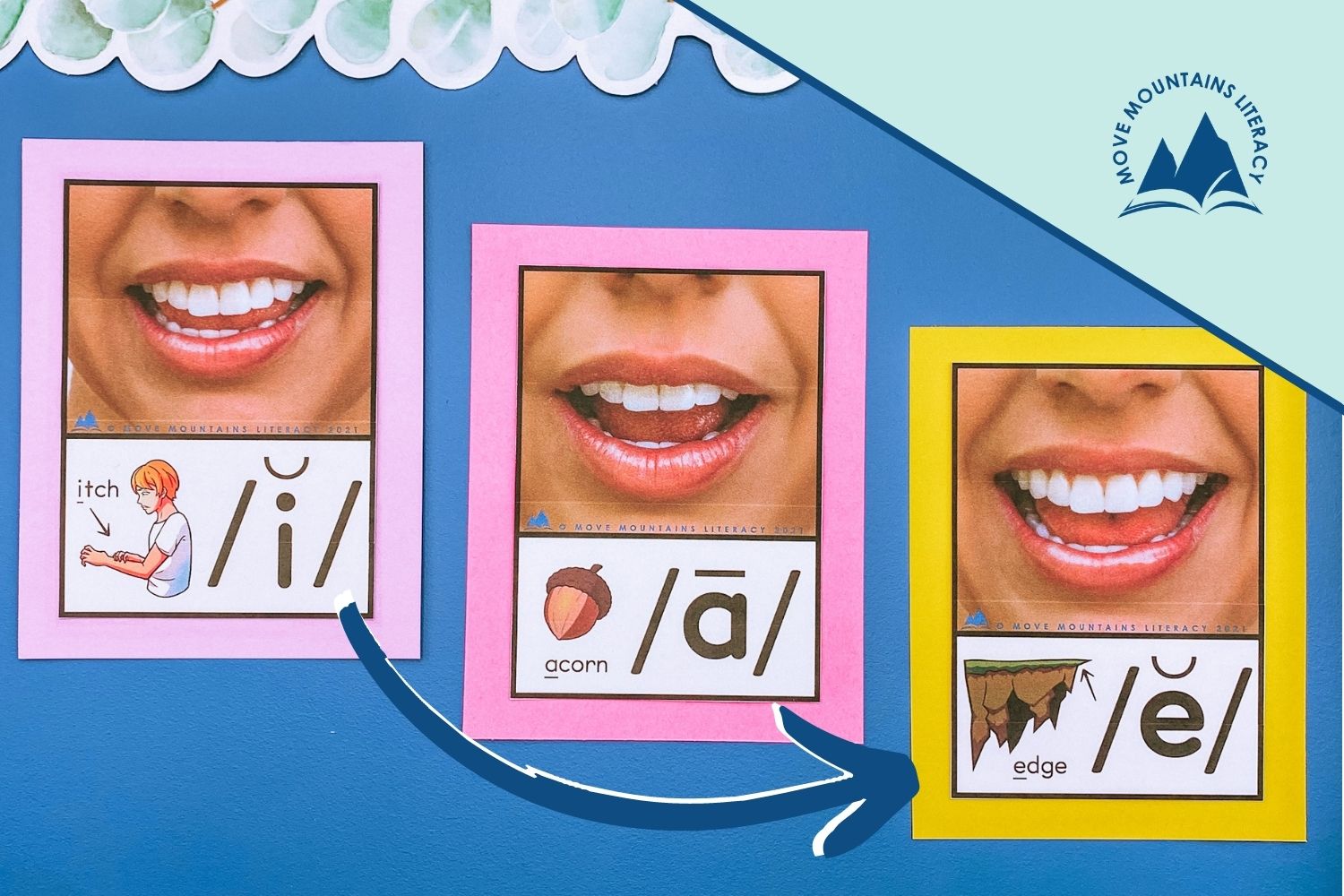

If you have had the privilege of teaching a primary grade level, you probably noticed your students struggling with vowels more often than consonants. The vowel sounds are challenging, and it’s no surprise. It is hard to distinguish their sounds because your teeth, lips, and tongue are nearly in the same position. Take short /i/ as in “itch” and short /e/ as in “edge” for example. Pay attention to your teeth, tongue, and lips as you alternate between these two sounds. You may have noticed a slight jaw drop and a shift of energy from the top of your mouth to your tongue. Bringing your students’ attention to these small differences will help improve their reading and spelling accuracy.

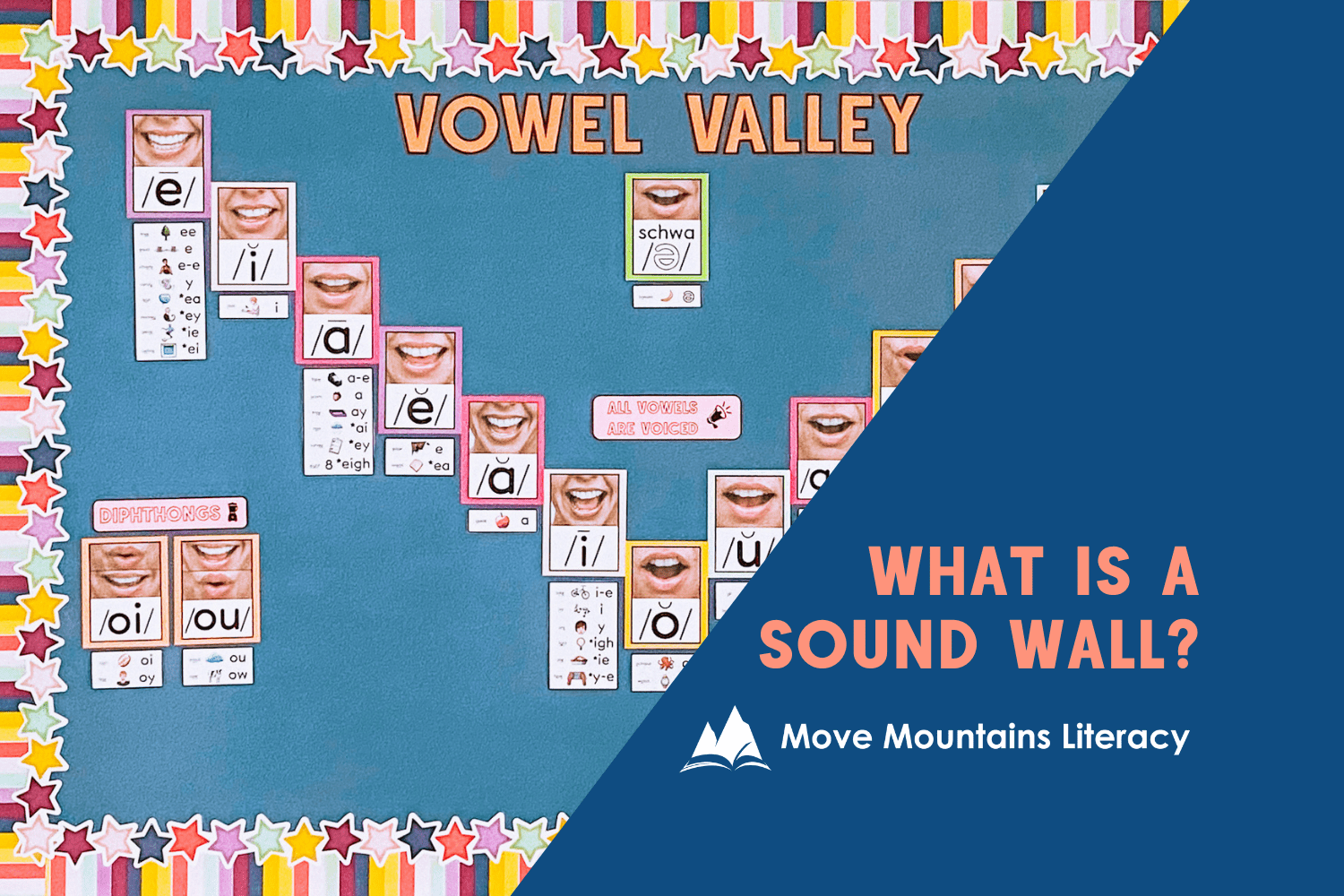

On a Sound Wall, the vowel sounds are organized in a V-shape. This shape is known as “Vowel Valley.” As you move from left to right, the sounds move from the front of your mouth to the back. Additionally, your jaw begins to drop as you move down one side of the valley and close as you move up the other side. It is important to note that the order of articulation of vowel sounds may vary based on dialect and accent. The order of articulation included in this blog post is consistent with the midwestern United States, following American Standard English guidelines.

The English language consists of eighteen vowel sounds. Two of those vowel sounds are diphthongs (/oi/ as in “coin;”/ou/ as in “out”). Three of the vowel sounds are represented by vowel-r (/er/ as in “fern;” /ar/ as in “car;” /or/ as in “fork”). The schwa describes an unstressed (unaccented) vowel sound. For example, the letter “o” in “lemon” is pronounced more like a short /i/, because it is in an unstressed syllable. To learn more about the articulation of sounds on a Sound Wall, watch the YouTube video above by Michelle Trostle.

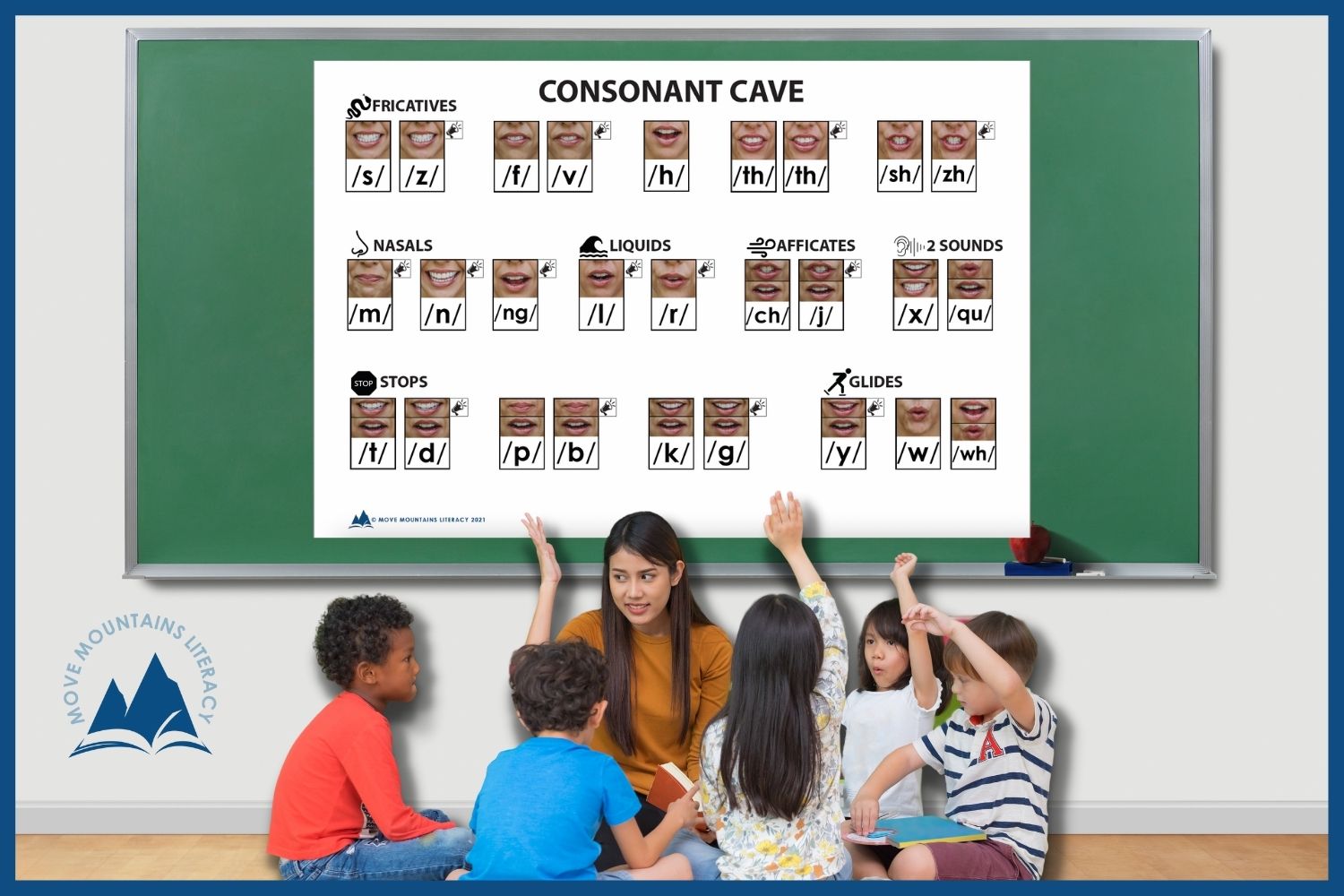

Consonant Sounds

Consonant sounds are organized by their manner of articulation or how the airflows when the sound is produced. Fricative sounds like /f/ or /z/ have a continuous airflow through an obstruction caused by your teeth, tongue, or lips. This obstruction creates a hissing or vibrating sound. Stop sounds like /p/ or /d/ refer to sounds where the air stops quickly after being produced. Nasal sounds like /m/ or /n/ refer to sounds where the airflow travels through your nasal cavity. Try plugging your nose while making the /m/ sound. Affricate sounds like /ch/ or /j/ refer to sounds created by a short burst of air followed by a hissing or vibrating sound. Liquids like /l/ or /r/ refer to partially obstructed sounds. The obstruction is not enough to cause friction. The air seems to float through your mouth like a liquid. Glide sounds like /y/ or /w/ have an open airflow like vowels, but their sounds do not create syllables in words. These sounds quickly glide into the sound that follows.

Please consider the age and ability of your students when teaching them about the manner of articulation. Remember that the goal is for students to recognize the distinguishing features of sounds and identify the sounds as vowels or consonants. The teacher should be familiar with terms like “fricatives” and “glides,” but it may not be crucial for students to memorize these terms to achieve reading success. Use your instructional time wisely.

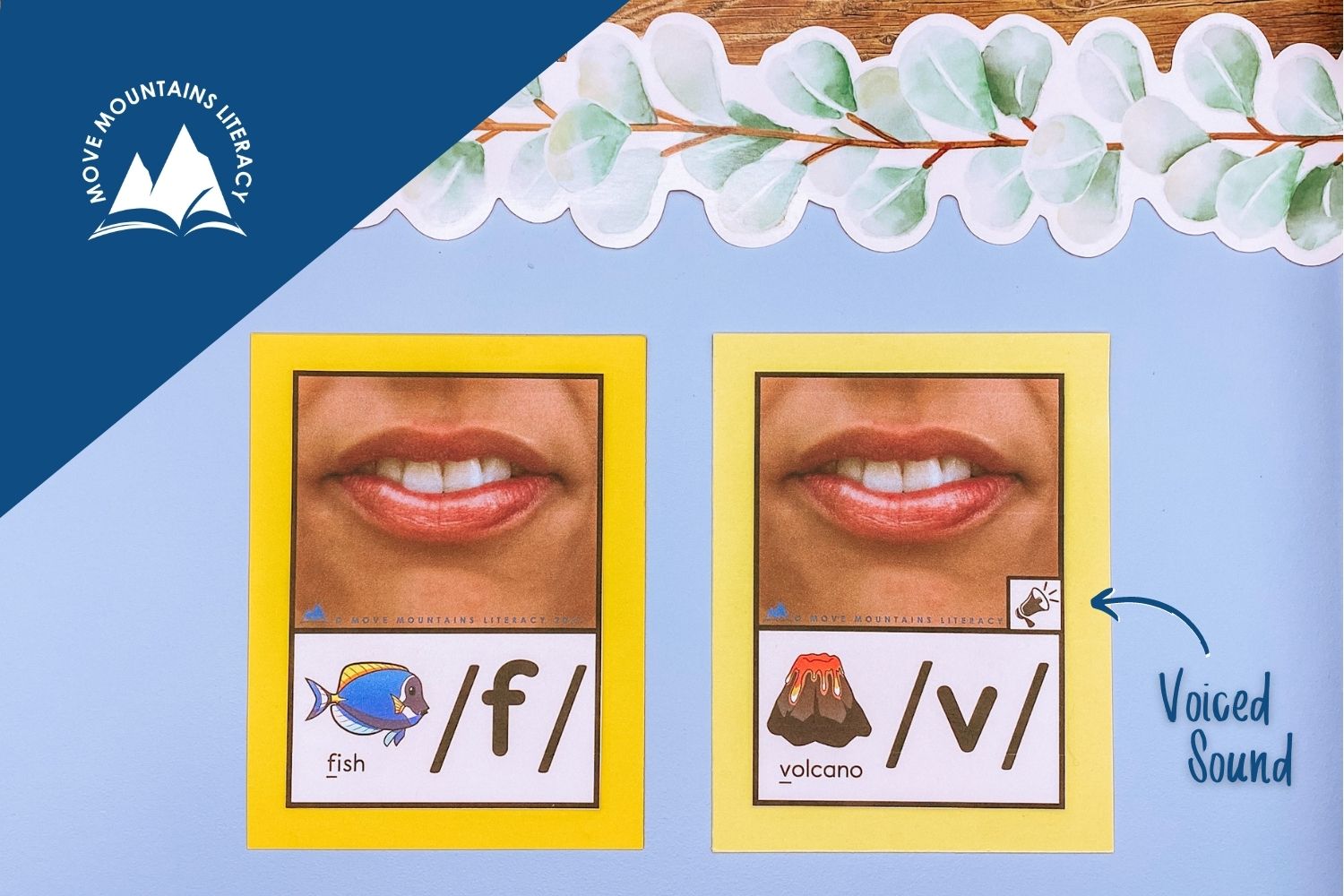

Within each category, consonant sounds are paired according to their place of articulation (position of the teeth, tongue, and lips). In the image below, you will find the /f/ and /v/ sounds paired together in the fricatives category. They are both fricatives because they are continuous sounds that cause a hissing or vibrating sound. The sounds are paired because they are produced with your top teeth resting on your bottom lip. However, /f/ is unvoiced. It does not cause your vocal cords to vibrate. The /v/ sound is voiced. It does cause your vocal cords to vibrate. Therefore, /f/ and /v/ are equivalents. Equivalents are sounds that have the same place of articulation, but one sound is unvoiced, and the other is voiced. As you can see, there are many equivalents in the various categories of consonant sounds.

The last category for consonant sounds is often titled “Two Sounds.” The first sound that falls into this category is /ks/ as in “fox.” The letter “x” is the only letter in the English alphabet that does not have a sound of its own. Instead, the letter “x” borrows its sounds from the letters “k” and “s.” The other letter combination in this category is “qu.” Like in many languages, the letter “q” is pronounced /k/. However, “q” is always followed by the letter “u” in English. Therefore, “qu” represents the /kw/ sound. Check out my “Sound Reference Guide for Teachers” to learn more about pronouncing consonant sounds.

Sound Wall with Mouth Pictures

A Sound Wall provides teachers and students with a framework to study the speech sounds in English and the letters (graphemes) that represent those sounds. A huge part of learning speech sounds requires students to attend to the place of articulation (teeth, tongue, and lips). Therefore, an effective Sound Wall will include photos of what the mouth is doing to produce each sound. Many Sound Walls also have an image, such as a megaphone, to indicate that the sound is voiced. These visuals help students work through an auditory process, making the abstract more concrete. Check out my “Sound Wall Mouth Pictures – Speech Articulation.”

“Good readers associate the sound segments of language with the letters in written words.”

Louisa C. Moats

Speech to Print

Sound Spelling Cards

Learning letter-sound correspondences can be challenging for students. Providing students with a familiar image can help them recall the sound represented by the letter(s). These images must represent the sound in its purest form. For example, a picture of an egg would not be a reliable representation of the short /e/ sound. Many people pronounce the “e” in “egg” like a long /a/ due to coarticulation. Coarticulation occurs when phonemes (sounds) are spoken close together, and the sound is distorted by the sound that comes before or after it. Use careful consideration when choosing images for letter-sound correspondences. Consider your students’ dialect and accent.

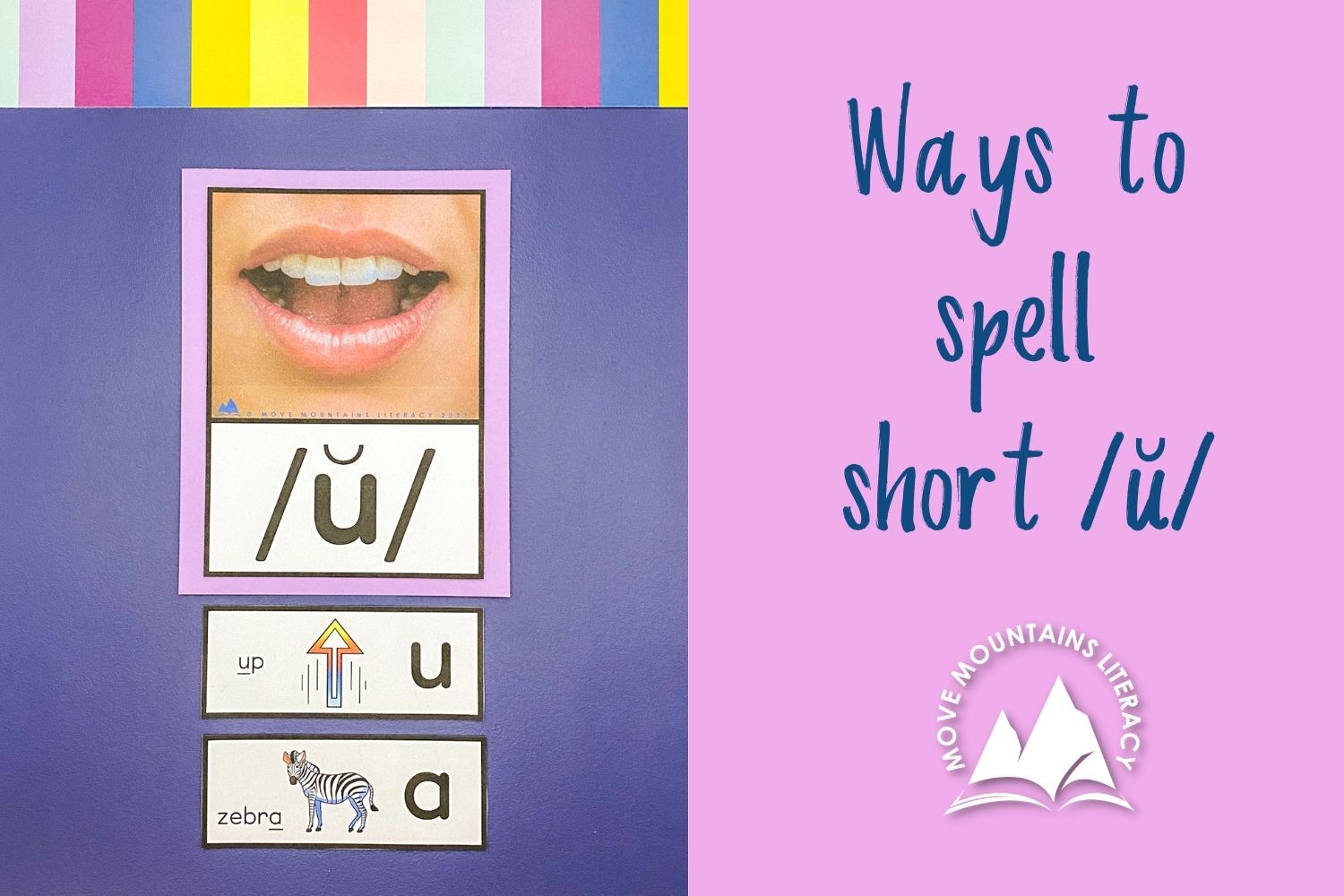

A Sound Wall also includes images that correspond with the various spelling patterns associated with each sound. For example, the short /u/ sound is spelled with “u” as in “up” or “a” as in “zebra.” In this instance, the teacher begins by teaching short /u/ is spelled with the letter “u.” The teacher adds the “up – u” card to the Sound Wall. Once students have mastered this spelling pattern, the teacher would teach that short /u/ is spelled with “a” in the final position of a base word. Then the teacher adds the “zebra – a” card to the Sound Wall. Check out my “Spelling Reference Guide for Teachers” to learn more about spelling patterns and phonetic spelling rules.

Sight Words

There are many considerations to make when adding words to a Sound Wall. Choosing the sight words and the order to introduce each sight word is often determined by the school district or the school’s reading curriculum. The following recommendations may seem lofty, only attainable in a perfect world. However, many school districts can make these adjustments to see significant progress in students’ sight word recognition abilities.

Educators define the term “sight words” in a variety of ways. For this blog post, sight words refer to high-frequency words that we want students to recognize instantly. Several teachers have used word lists developed by researcher Edward B. Fry and colleagues. Fry composed a list of the most frequent words found in printed material and ordered them according to their frequency. He found that the first one hundred words make up 50% of printed material (Fry, Kress, & Fountoukidis, 2000). Therefore, primary teachers aim to teach the first 100 words on Fry’s list as soon as possible. It is recommended to introduce 3-5 sight words each week. Check out this FREE Fry’s Word List to learn more about sight words and their order of frequency.

When looking at a list of sight words, the reader will find that some words are easy to decode and read. Other words appear more complex and may not seem decodable at all. Determining where a sight word falls on the regular to irregular word continuum depends heavily on the teacher’s knowledge of the English language rules. Ultimately, words that are more regular for reading belong on a Sound Wall. This makes the Sound Wall reliable when students reference it for reading or spelling assistance.

In the past, educators have resorted to rote memorization of irregular sight words. Research has shown more effective strategies for teaching irregular words to students. It is recommended to use an approach often referred to as the “Heart Word” method. Essentially, teachers walk students through an in-depth look at the word and identify the part of the word that is irregular. Teachers may choose to keep irregular words separate from their Sound Wall. Consider creating a separate space to display “Heart Words.” To learn more about the “Heart Word” method, visit Really Great Reading.

After you have compiled your word list, determine the order in which you will introduce the sight words. Some school districts teach sight words in the order of frequency, beginning with the most frequent words. Unfortunately, the words that come up in the lesson plan don’t always coincide with what the students are learning that week or what they have learned previously. Therefore, consider the students’ prior knowledge and classroom instruction each week. Have the students learned the letters or letter patterns in the sight word? Are there sight words that follow the spelling pattern students are studying this week? Work with your school’s administrators, reading specialists, and curriculum writers to develop a well-thought-out scope and sequence for introducing sight words.

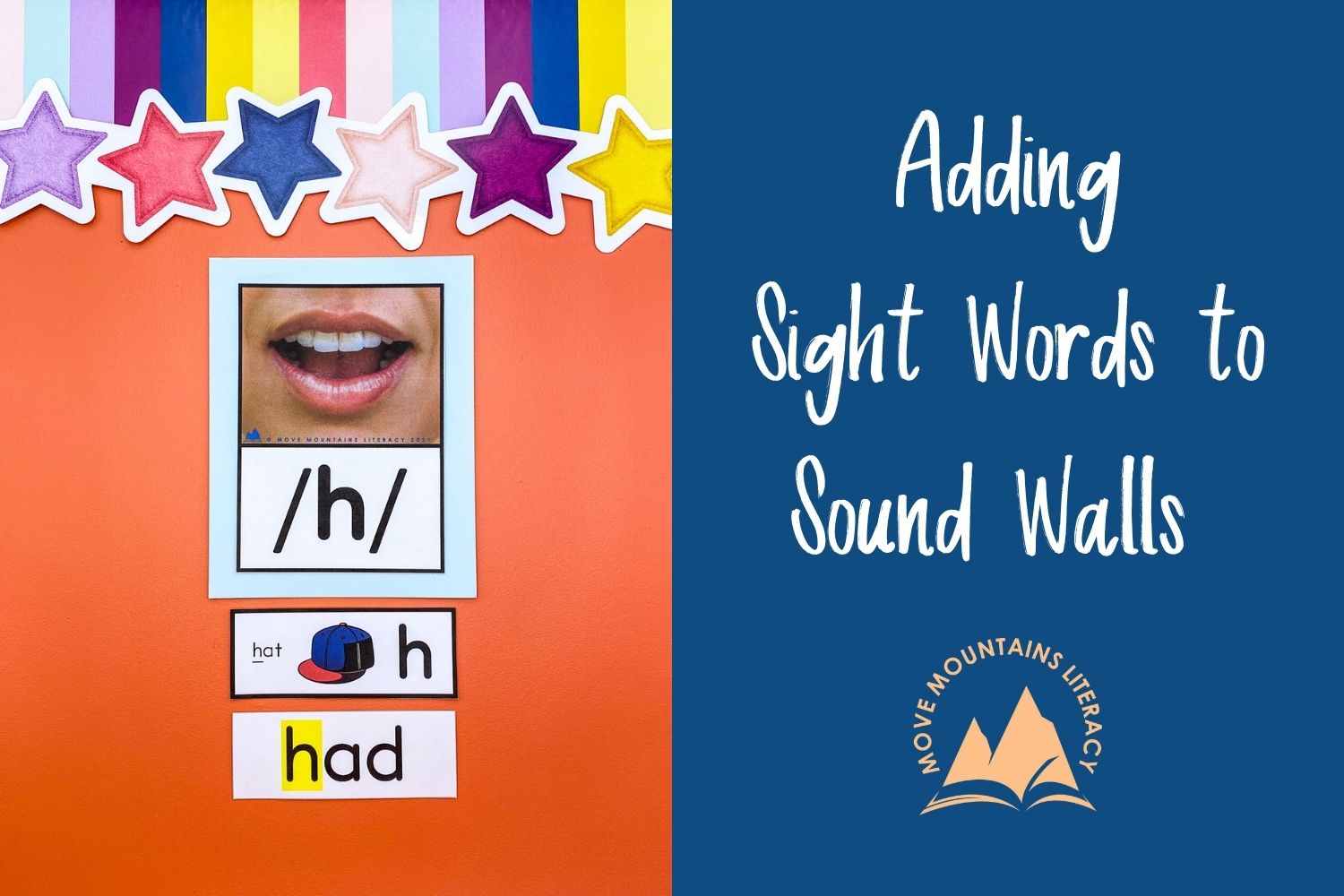

The last step is to add the sight word to your Sound Wall. Some teachers find the freedom and flexibility of adding high-frequency words to a Sound Wall overwhelming. Words can be placed according to the first, last, or middle sounds. For example, the word “had” could be placed under /h/ or short /a/ or /d/. If the students have learned short /a/ and /d/, but the letter “h” is a new concept, the teacher may choose to place “had” under /h/. If students struggle to attend to the final sound in words, the teacher may choose to focus their efforts on the letter “d” and place “had” under /d/. For more examples and a deeper explanation on adding words to a Sound Wall, check out my blog post: “How to Use a Sound Wall.”

Sound Wall Cards

Begin implementing a Sound Wall in your classroom today! The Sound Wall Bundle featured in this post includes mouth articulation photos, letter-sound picture cards, sound spelling cards, and student Sound Walls. These products are also sold separately.

Want to learn more about Sound Walls? Visit the blog posts below: